Alejandra Burchard Levine

Advisor Environmental and Social Assessment

On November 3, 2025, NCEA facilitated an online exchange between the coastal cities of Beira (Mozambique) and Recife (Brazil) that revealed insights about the gap between ESIA planning and on-the-ground implementation. Twenty-two participants from seven institutions, mostly municipal staff, shared honest experiences about what it really takes to translate ESIA commitments into resilient, community-supported infrastructure.

The timing was strategic: Beira has completed its ESIA for coastal protection in 2024 and stands at the threshold of implementation, while Recife is midway through its landmark US$260 million ProMorar resilience program (2023-2029). This unique pairing—one city learning before implementing, the other systematising hard-won lessons—created a powerful space for mutual learning about what makes ESIA processes genuinely effective in vulnerable coastal communities.

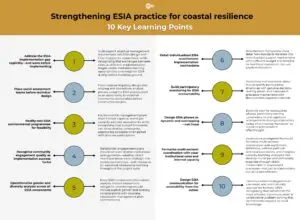

The session produced many valuable lessons on better ESIA. Read the 10 most important takeaways below.

“I was particularly impressed by how Brazilian institutions approach community engagement. They have had the space to test and validate different models of social involvement adapted to specific community groups. Beira has much to learn from this culture of participation.

Another notable strength is the alignment of initiatives with local municipal regulations and clear definition of institutional roles—with the municipal assembly playing a strategic role in enabling reforms to bylaws, which is essential for institutional maturity. Regarding Environmental Impact Assessments, we recognize these remain largely under the exclusive domain of formal consultancies, with limited space for internal capacity building within the municipality or civil society—the technical knowledge tends to remain external.”

Hélder Domingos, FACE Association (Beira)

What’s Next

The NCEA is exploring options to continue this South-South exchange as Beira moves into implementation of its coastal protection project. Future discussions could focus on facilitating dialogue around the roles of different government layers and institutions, with particular emphasis on community-led initiatives.

Also, the NCEA has invited participants to share input on potential format, periodicity, and priority themes. The 38 questions identified during the exchange—from organising community participation in 12 kilometres of dune vegetation to managing construction-to-management transitions offer a rich foundation for possible future sessions. As this collaboration takes shape, The NCEA remains committed to supporting exchanges that strengthen ESIA practice for resilient and equitable coastal infrastructure.

Picture:©NCEA – Alejandra Burchard Levine

This link opens in a new tab This link opens in a new tab |

Recife’s experience showed that even well-designed ESIAs require significant refinement during execution—planned programmes proved inapplicable, new needs emerged, and community demands evolved. Beira’s strategic position—having completed ESIA but not yet begun implementation—offers a rare opportunity to integrate these lessons proactively.

ESIA implication: Build explicit adaptive management mechanisms into ESIA design with clear triggers for adjustment, while recognising that exchanges between cities at different implementation stages create invaluable learning opportunities to strengthen ESIA quality before breaking ground.

Recife’s breakthrough places social teams in communities before infrastructure design, spending two months in co-creation that produces “Project Guidelines.” Beira’s strategic position—completing ESIA before implementation—offers the opportunity to integrate these lessons from the start.

ESIA implication: Front-load participatory design into scoping and alternatives analysis phases, using the ESIA process itself as an opportunity to establish community relationships before construction begins.

Both cities demonstrate how resource constraints drive innovation. Recife tested nature-based solutions like filter gardens that technically worked but proved financially unfeasible for municipal maintenance. UN-Habitat’s Espangara Project in Beira turned budget constraints into opportunity, using participatory planning to identify nature-based solutions that communities could maintain.

ESIA implication: Environmental management plans must include rigorous municipal capacity and cost assessments, while recognising that budget limitations can drive creative, community-appropriate solutions when paired with genuine participation.

Participation fundamentally determines whether infrastructure achieves resilience objectives. Recife’s constant community presence through local offices and door-to-door work builds trust for difficult decisions. Beira’s FACE Association demonstrates an alternative model: a community NGO acting as strategic bridge between municipality and communities, reaching where government cannot through social marketing, focus groups, and community action methodologies.

ESIA implication: Stakeholder engagement plans should consider diverse institutional arrangements—whether direct municipal presence or strategic civil society partnerships—with resources for sustained relationship-building throughout the project cycle.

Recife demonstrated how gender and diversity considerations cut across all implementation aspects—from women’s safety in urban design to productive inclusion in construction to children’s participation.

ESIA implication: Every ESIA component (alternatives analysis, impact assessment, mitigation, monitoring) should include explicit gender and diversity considerations with concrete, measurable management plan commitments.

Recife applies IDB international standards (“equal to or better than”) through individualised assistance with multiple options near original locations. The principle: “remove the risk from the area, not necessarily the people.”

ESIA implication: Resettlement frameworks must detail how standards translate into individualised support mechanisms with sufficient budget and timeline for livelihood restoration, not just physical relocation.

Recife’s construction monitoring committees with community residents, local social offices, and grievance mechanisms create real-time feedback loops allowing rapid course correction.

ESIA implication: Monitoring and evaluation plans should specify participatory structures with genuine decision-making power and transparent grievance mechanisms with documented response protocols.

Recife’s five dynamic phases deliberately overlap. Shared management begins during construction, not after, challenging typical ESIA phase thinking.

ESIA implication: Explicitly plan for overlapping phases, particularly starting community co-management arrangements during construction rather than treating “handover” as a post-implementation afterthought.

Recife demonstrates clear definition of institutional roles, with municipal assemblies playing strategic roles in enabling bylaw reforms. Beira’s experience highlights both opportunities and gaps: FACE Association shows how civil society partnerships can extend municipal reach, while participants honestly recognised that “the community still does not have a privileged place at the decision-making table” and that “processes need to mature” with necessary depoliticisation. ESIA expertise often remains with external consultancies, limiting internal capacity development.

ESIA implication: Governance arrangements should formalise multi-sectoral coordination with explicit role definitions, address political-technical boundaries, and integrate capacity-building strategies that develop municipal and civil society expertise through direct involvement in assessment processes—not just as stakeholders, but as co-practitioners.

Technical ESIA reports fail to reach communities with varied literacy levels. Recife uses models and virtual reality for validation consultations. Beira’s FACE Association employs adapted social marketing approaches and door-to-door surveys that meet communities where they are. Their co-creation methodology—identifying existing community actions, improving together, reusing local materials—demonstrates communication through action, not just words.

ESIA implication: Communication strategies must use visual, oral, and culturally appropriate formats, while recognising that sometimes the most effective “communication” is collaborative problem-solving that demonstrates respect for local knowledge.